Moby Dick is a huge novel. A masterpiece of literature with a gripping plot, a cast of amazing characters, a mythic monster, themes of life, death, vengeance, industry and the questioning of an interventionist god. A road movie on a ship with an obsessive sea captain, a noble pagan, a pious first mate and a young adventurer and supporting characters that include a drunken landlord, a ragged docklands prophet, a happy-go-lucky second mate, a pugnacious third-mate and about twenty five other motley crewmen. All against the backdrop of a whaling voyage across three oceans and as round an education in the business of nineteenth century whaling that you could wish for. All this and some of the most fluid, beautiful and romantic descriptive writing ever put to paper. “It was a clear steel-blue day. The firmaments of air and sea seemed hardly separable in that all pervading azure. Hither and thither on high glided the snow-white wings of small unspeckled birds. These were the gentle thoughts of the feminine air. But to and fro in the deep, far below in the bottomless blue, rushed mighty leviathans, swordfish and sharks; and these were the strong, troubled, murderous thoughts of the masculine sea.”

Moby Dick is a huge novel. A masterpiece of literature with a gripping plot, a cast of amazing characters, a mythic monster, themes of life, death, vengeance, industry and the questioning of an interventionist god. A road movie on a ship with an obsessive sea captain, a noble pagan, a pious first mate and a young adventurer and supporting characters that include a drunken landlord, a ragged docklands prophet, a happy-go-lucky second mate, a pugnacious third-mate and about twenty five other motley crewmen. All against the backdrop of a whaling voyage across three oceans and as round an education in the business of nineteenth century whaling that you could wish for. All this and some of the most fluid, beautiful and romantic descriptive writing ever put to paper. “It was a clear steel-blue day. The firmaments of air and sea seemed hardly separable in that all pervading azure. Hither and thither on high glided the snow-white wings of small unspeckled birds. These were the gentle thoughts of the feminine air. But to and fro in the deep, far below in the bottomless blue, rushed mighty leviathans, swordfish and sharks; and these were the strong, troubled, murderous thoughts of the masculine sea.”

Our adaptation, made by co-artistic director Judy Hegarty Lovett (the director) and myself (the actor) is almost 16 A4 pages. It runs approximately 2 hours of stage time with a 15 minute interval.

So what brings one to attempt to put on stage one of the great, great works of world literature?

The impetus to do this is easy to explain. Judy and I, through our company, Gare St. Lazare Players Ireland have already presented ten prose pieces by Samuel Beckett for theatre audiences. With a good deal of success. Of these only three were full length novels. Of these, one - Molloy, the first one we did – is almost an entire 10 or 12 page section from early in the first part of the novel. With the other two – Malone Dies and The Unnamable – we began at the beginning and ended at the end and tried to give a good sense of the in between but its fair to say that the plot in each case, how shall I say, wasn't the most important aspect of the novel. In each case we don't consider them adaptations and we never wrote, let alone uttered, a word, not to mind a sentence, that Beckett didn't write. These versions, and the subsequent presentation of them which we have toured extensively in a show entitled The Beckett Trilogy, we are really very pleased with. Our impetus has always been to share with an audience writing that has moved us profoundly.

Both Judy and I read Moby Dick for the first time in 2008. We came to the novel knowing very well that John Huston's 1956 movie version was made in Youghal, Co. Cork, Ireland, about an hour from where we grew up in Cork City.. Judy read the novel first and raved about it to me. She was about halfway through it when she suggested we do it for the stage. I remember thinking I'd better read it then. We originally thought about asking a writer to adapt it, someone who could make sure the final script had a good arc to it. Then we decided we should do it ourselves. We felt that with our prior experience we could serve the work well and could best bring our original love for it directly to an audience. It would be easier to make changes quickly in rehearsal and we felt well equipped as we'd have a good sense of what would and wouldn't work theatrically. After all with a writer like Melville (as with Beckett) the best work had already been done.

By premiering the work in Youghal we paid tribute to another adaptation of this remarkable American work. We are also marking the huge impact that Huston's movie project had in the recent folklore of that town and in Ireland. As the cinematic version of the Pequod was launched from that port so too did our theatrical version set sail from there.

The process of working on Moby Dick has been much the same as our usual. I learn the text and then Judy directs me. We spend hours rehearsing and laughing and arguing and discussing and marvelling at the awesome skill and breadth and vision of this amazing writer. At this point in time to reflect on it is interesting. I remember how in the rehearsal process I had forgotten how to act and I had forgotten why we were doing this. In the thick of rehearsal it is easy to lose sight of one's own vision. Gare St. Lazare's vision is about making the text your own so that you perform it as if it is your words, your story, your truth. In this way the actor and director appear to disappear and the audience is left, we hope, with a direct link to the writer. This process cannot be done by an actor alone nor by a director alone. Luckily I work with a patient and brilliant director who never loses sight of this vision and is devoted to acting and writing and teaching.

And in bringing our work to New Haven again we are especially thrilled to be joined on the voyage by one of Ireland (and the world's) most exciting musicians, Caoimhin O'Raghallaigh. This is our first time working with Caoimhin and it is entirely fitting that this new collaboration takes place at the International Festival of Arts & Ideas. My experience at the festival last year has shown me that it is a unique and special festival (I've been to quite a few!). The festival and its team champions art, ideas and humanity in equal measure and the honour to be invited back so soon is one that I cherish.

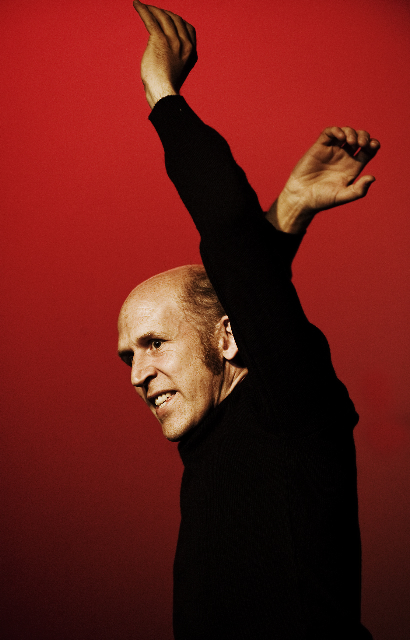

Conor Lovett.