Stephanie Burt grew up in the 1980s reading science fiction and X-Men comics. "I was treated as someone really nerdy, who liked video games and was really into science and loved Star Trek and X-Men comics, which was correct—and as a boy, which was wrong," she says. "But I didn’t have the language to say, 'No, that's wrong.' I was very confused."

That sense of yearning confusion pervades Burt's poetry collection Advice from the Lights (Graywolf Press, 2017), a candid exploration of gender and identity that asks: How do any of us achieve adulthood? In her critically acclaimed collection, Burt engages with the transition from innocence to experience, contemporary politics, and parenthood. Her poems are fraught with fantastical sequences in which objects speak and animals grapple with their identities. This essential work asks who we are, how we become ourselves, and why we make art. Arts & Ideas has selected Advice from the Lights as its choice for 2020 Big Read, an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest.

Stephanie Burt is a poet, literary critic, and professor. In 2012, the New York Times called Burt “one of the most influential poetry critics of [her] generation.” She has published books of criticism and four collections of poems; her book Close Calls with Nonsense: Reading New Poetry (2009) was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and she is a Professor of English at Harvard University.

Arts & Ideas talked with Burt about how science fiction led her to poetry, her kinship with Mr. Spock, and her affinity for mole rats.

Childhood experiences echo throughout this collection. Could you talk about how the culture and environment of your childhood play into your current work?

I grew up in an extremely safe space in a lot of ways. I was supported without being understood; my parents did everything they could to give me a happy childhood, and it didn't exactly work because the vocabulary we have now for talking about kids like me was simply not available then.

Now, I can look at some young people I know and say: That is a binary trans girl who is not clinically autistic, but neuro-diverse in other ways. We can also say that the way we expect children to self-segregate by gender in grade school is a load of hooey, and that we shouldn’t do it. We know how to say that now—but not in 1981. I didn’t really get a chance to be who I am until this decade.

I remember thinking I was like Mr. Spock from Star Trek because the way neuro-typical human beings behaved didn't make sense to me. Not only does Mr. Spock want things to be logical and make sense in the way that they don't—not only is he capable of deep and sometimes sexual affection in ways that people around him don't quite understand—but he's neither conventionally masculine, nor conventionally feminine. He doesn’t do boy things, but he can’t do girl things.

When did you begin writing poetry?

Before I high school, I wanted to be a science fiction short story writer like Samuel R. Delany. I read a lot of science fiction, and I didn’t read any realistic fiction because I didn’t see myself in it. In the science fiction that I was reading—from the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s—there’s a lot of cohesion to high culture literature; for instance, on the first page of Samuel R. Delany’s novel The Fall of the Towers, he quotes the poet W. H. Auden.

In this era of science fiction, you are constantly encountering canonical poetry in bite-size units, so I figured I had better read some canonical poetry to figure out how to be a science fiction writer. It turned out that I was better at writing the kind of poetry that high school teachers like than I was at writing the kind of science fiction short stories that anyone else wanted to read.

That's a great transition into your poetic language and the imagery that reappears throughout your book; not just the childhood references, but also insects and animals, like in the poem titled "To the Naked Mole Rats at the National Zoo." What's your fascination with bugs and bizarre creatures?

Well, the first poem in the book is spoken by a block of ice—and the great thing about talking blocks of ice and mole rats is that I’m not appropriating their stories. I have certain things in common with the stories and struggles and feelings of actual historical and fictional characters who are, for example, African American or South Asian—but I don't really want to write in their voices, for reasons that in 2019 should be obvious.

The idea that I can see myself without having to tell a life story—either mine or somebody else's—is really attractive to me. There's a long tradition of that; I love the Elizabeth Bishop poem, “Song for the Rainy Season,” for example. I really see myself in that frog.

How do you want your poetry to be described?

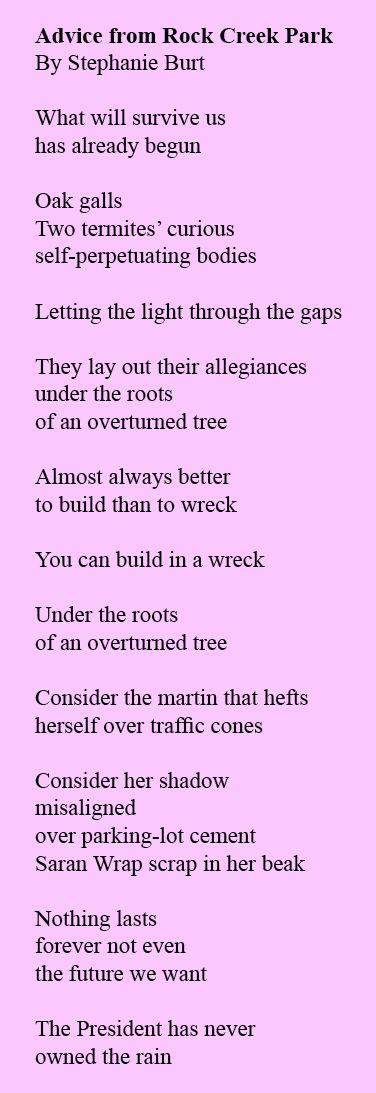

The kind of poetry that I want to write is about gradual change and comprehensible change, both emotionally and socially. Because I'm a white lady and I have white privilege, like it or not, I have doubts sometimes about whether that aesthetic and point of view, and that way of writing, is adequate to our society and the moment we are in. There are a couple of poems near the end of Advice from the Lights that speak to that; the poem "Concord Grapes," in particular, which is about the fact that we're all living in a stolen land, unless you're native. How much should we do about that, and how much can we do about that, if we are not ourselves native?

The shape of the book was almost finished, and it was already had a publication date, when the current president was elected. I realized that the book should end not with a vision of adulthood, but with a vision of social wreck. What do you do when your sense of the possibility for a just society has just been set on fire?

Although your poems do not rhyme, you do often rhyme the final two lines. What do you hope to achieve with the introduction of that formal style at the very end of a poem?

I love rhyme; I like closure. There’s a strain of thought in contemporary American poetry that says closure is bad, that it feels like a poem clicking shut like the clicking of a box, and that it is intellectually dishonest and somehow Republican. I don’t think that's true at all. I think it indicates that the poem is not the entire world, and that things might make sense, that resolution is possible, at least formally. That's emotionally useful to me. I find it beautiful and even ethically useful because we need to be able to imagine solutions sometimes.

Arts & Ideas partners with NEA Big Read to host a series of community events focused on a single book as a point of departure for conversations throughout New Haven. An initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest, the NEA Big Read broadens our understanding of our world, our communities, and ourselves through the joy of sharing a good book. Learn more and find out how to organize an event around Advice from the Lights >