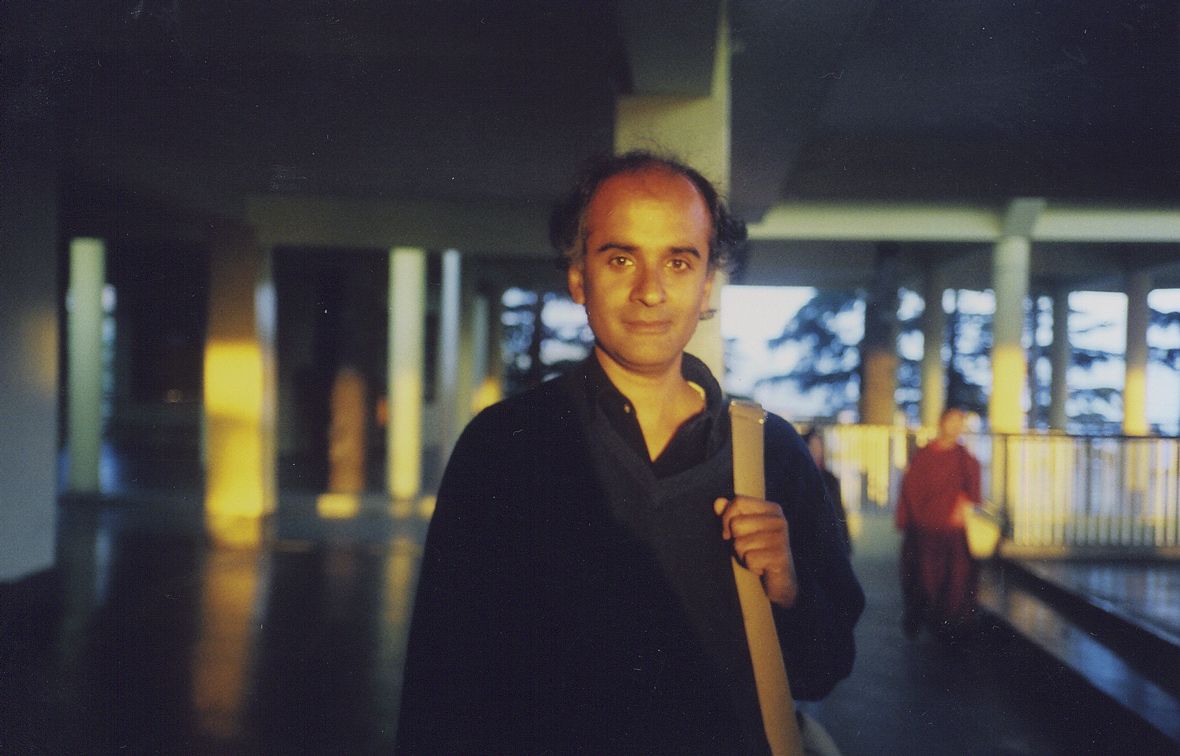

As previously mentioned on this blog, I am a podcast junkie. While scrolling through the past episodes of one of my favorite shows, Krista Tippett’s On Being, I came across an interview with Pico Iyer, whose work I admire greatly and who I’m so thrilled will be joining us as an Ideas speaker for When Are Houses Are Not Homes on June 16th. I immediately downloaded and played it. Krista Tippett is a wonderful interviewer who researches thoroughly and asks questions with uncommon sensitivity and intelligence, but Pico more than proves her equal as interviewee. While I’m no Krista Tippett, I decided to use the occasion of his visit to New Haven to ask him some questions myself.

AR: In the Festival this year, and particularly in the Ideas series, we are focusing on the interconnected themes of home, immigration, and displacement. You’re a travel writer who moves a great deal internationally, and you’re connected personally to a number of places across the globe that you might call “home.” How do you find stability and stillness in a life and profession that seem to have you always on the move?

PI: That’s a wonderful question, and it’s certainly true that the more some of us spin around the globe—or find the globe spinning around us—the more we need an anchor. Never in all of human history, I would say, has stability been such an urgent necessity than in our age of distraction and acceleration.

Some of us are scattered across the globe, seeming to live in a dozen time-zones all at once; some are simply scattered because more information is coming in on us every day than came in on Shakespeare in his entire lifetime. And some are taking in all this data even while flying from continent to continent—just to visit our loved ones, or to do our jobs—and in the process becoming doubly dizzy.

Disconnection squared!

So even those of us who seldom leave our hometowns know that we can’t survive without something changeless and grounding to hold onto. In my case, I have, wherever I am in the world, an image of my mother and my wife in my head (and, nearly always, the chance to be in close touch with both of them). A picture (in my mind) of the monastery to which I’ve been returning regularly for more than a quarter of a century. A favorite song close to hand, a beloved book, a belief that I know will never desert me—and a sense of destination, and what I wish to be moving towards.

And all those help me to feel myself, and at home, even when I’m flying, as sometimes happens, from California to Japan to Europe in the space of four days.

It’s true that I’ve moved a lot in my life, having begun commuting to school by plane, alone, from the time I was nine years old. But for seven months every year, I live inJapan, where for three months on end I seldom leave my neighborhood (my wife and I have no car or bicycle, we receive no newspapers or magazines, and we don’t even have a living-room or real bedroom in the rented, two-room flat we’ve occupied now for 23 years).

My daily commute there involves a fifteen-foot walk from my bed in one corner of the apartment to my desk in the other. My afternoons involve taking leisurely walks around the neighborhood. My nights find me, while I’m waiting for my wife to come home from work, turning off all the lights, and listening to some music.

It’s only through these periods of extended stillness that I can begin to race across continents at high speed at other times; to me it feels like breathing in and breathing out, flinging myself out into the world to take in all its challenges and stimulations, before sitting very still for a long time to make sense of them and try to find their meaning. Given that our lives are almost visibly accelerating with every season, and growing more dispersed and all-over-the-place, I think everyone I know is finding ways to anchor himself or herself, in ritual or personal commitment or community.

Some by going for a run every day, some by meditating, some by cooking or playing golf or reading: anything that will give us a larger frame for the stuff that keeps flooding in one us.

Movement, in the end, is only as deep as the stillness that lies beneath it. And it’s only in stillness that we can take the raw stuff of life—our encounters, experiences and emotions—and turn them into a full meal. It’s hard to be moved, in the deepest way, except when you’re sitting still.

So I tend to see travel as the way I make my living and build the house of my existence; and stillness is the way I lay foundations under that house, and make my life.

AR: Speaking of peace, I know that you don’t have a defined religious practice yourself but that you take great interest in spirituality and reflection. Do you feel that this is difficult to maintain in a world increasingly glutted with new devices, improved technology, and expanded modes of communication? Do you feel it’s possible to be both at peace and linked in, or is sacrifice one way or the other inevitable?

PI: I do feel that it’s possible to be at peace and connected at the same time—indeed, that it’s essential to be both deeply in the world and at some level removed from it simultaneously simply to do justice to those two mighty partners, the self and the world.

Silence and connectedness are not opposites so much as separate parts of the same equation (the monks at the Benedictine hermitage where I’ve been spending a lot of my life for 25 years are online so much that their system frequently crashes!). Our connections, after all, are how we bring material into our life to make sense of, and silence is how we process all that information and then head back out into the world with greater purpose and clarity.

The important thing, perhaps, is just to remember what “connection” means, and to recall that it refers to something far deeper than planes or phones. And not to let all the data and distraction in the world get in the way of what we care about and what keeps us human.

To me technology is not good or bad, sacred or profane; it’s simply a tool or medium by which we can pursue our own ends, exalted or less so. And for many people today technology is how they can listen to sacred music, see images that still them with their beauty, keep in touch with counselors, fly (as I did last week) to visit Thomas Merton’s Gethsemani.

Technology is an extraordinary blessing for which I give thanks daily. Without it, I would never have been able to visit the holy churches of Ethiopia, or to listen to Krista Tippett, or to drive up to my local monastery.

The only danger comes when we confuse means with ends, and, as Thoreau memorably put it, become tools of our tools. If we start to prefer the online world to the “real” world, like those in Plato’s cave, or if we get so caught up in our virtual universes that we forget the ones knocking at our door and crying inches behind us, then we are using technology as a way to escape what is real rather than to travel deeper within it.

But the problem is never with our machines, I think, and only with ourselves (and our failure, at times—I know from my experience—to be as wise and clear-sighted in our use of them as we could be). Sometimes I look up after watching four straight movies on a plane, and wonder where I’ve been, what exactly I’ve done and who I am. Especially since there’s a deluge of conference-calls, e-mails and running around awaiting me the minute I land. But I realize the only culprit for keeping me dizzy on the surface of things and far from the soul is—as always—myself.

AR: Writing seems to me a practice that makes possible any adventure that the imagination can conjure up within a quiet, solitary, and perhaps even meditative process. In what ways do you find writing either a familiar safe haven or a wild journey – or both?

PI: Writing is indeed the one home I know—a cabin in the woods, a sanctuary, the contemplative space into which I can retreat every day, to make sense of all I have experienced—and the great adventure that life has afforded me. In that sense, it offers all that most of us look for in a partner, a home and a living: a mix of the familiarity we need to ground us and the constant surprises we need to keep us alert, alive and engaged.

I often think that writers are lucky insofar as we are paid (or at least encouraged) to sit still for hours every day, in the kind of stillness that others have to seek out consciously as meditation; and, like any journey into the dark—even the wilderness—it cannot fail to be a wild adventure. Nothing I have seen in Ethiopia or Paraguay or Easter Island can quite compare with the strangeness and intensity I know when I’m at my desk, alone with my thoughts—and imaginings and memories—for day after day, and savoring that drug that Hunter Thompson called more transporting than anything he’d physically ingested.

This also of course can make writing harrowing, unsettling and lonely, as one confronts, without distraction, the dark spots in one’s life and in the world. But better to do so at one’s desk than unprepared, and though writing can be torment, it’s always the most joyful and worthwhile torment I can imagine. It reminds me of when Herbert God called Haiti “the best nightmare on earth.”

I feel hugely blessed that I do have this safe space (in the imagination) to which I can return every day, and that writing can be a portable home I carry everywhere with me, much as others might carry a Bible or a prayer. And I understand why the likes of Graham Greene say that they can’t understand how most people can function without the therapeutic mirror and release of writing: when I was spending five weeks in an I.C.U. last year, as my mother teetered between life and death, I felt grateful every hour for the writing that, every day, allowed me to step out of the hospital wards (in my head), to try to understand and record everything that was happening, and so to gather the resources that I would need to sustain myself and support my mother.

Not long ago, I stopped writing books for four years, because I wasn’t sure that books were the medium of right now. And then, at some point—belatedly, I’m sure—I realized I was doing myself out of the greatest joy and adventure, the most pleasurable passion, my life had offered me.

So I scurried back to my publishers, signed on to write two more books, and felt that, whatever was going on in my life or the world, at least now I had something to excite me, and keep me surprised and excited every day of the year.

- Alex Ripp, Ideas Program Manager