With a gun to his head, Toto Kisaku was moments away from being killed by his government when his executioner showed him a moment of mercy. His only crime? Creating art that questioned the practice of child exploitation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kisaku arrived in the United States in late 2015 seeking political asylum, which he was granted in March 2018. He premiered his play Requiem For An Electric Chair, about the seven days he spent in that dark cell, at the 2018 Festival with three sold-out performances.

Our 2019 Artist in Residence and the founder of K-Mu Theater, Kisaku creates work that focuses on transcending the constraints of daily life and examining how people living in poverty or under oppressive regimes can recreate their environments and improve their lives through the arts. In honor of his final week as our artist in residence, we sat down with him to talk about the play that brought him to the United States, how he has embraced his new community, and what we can expect to see from him next.

How did you become involved with the children who were being exploited in the Congo?

I found there were 25,000 kids abandoned in the streets of Kinshasa. I didn't have a very good childhood, and I wanted to do something for those kids, not just working with them, but understanding what was bringing them into the streets. So I started questioning community leaders, and I understood there were three different problems: The first is poverty; people could not take care of their kids.

Then, churches: pastors were selling utopia to the people, telling them that if they brought money to the church, then the pastors would pray for them. If they didn’t have money, then they should find the evil in their families—the innocent kids—and bring the children to the church, where the pastors will pray for them. But the pastors did not do that; they beat the kids. And the children ended up on the street.

The third party taking advantage of these kids was the government, because the more people are ignorant, the more the government has the power.

What did you do to help these kids?

There are many organizations who care about these kids, but they can only help 10 or 20 of them. But 25,000? How can you resolve that? I decided to create a campaign to inform people.

I connected with a director friend from the Netherlands. We found there was a law voted by Congress that protected kids, but was not enforced. We used that law to inform people. We did more than 100 performances in front of 2,000 people in each production. More than 150,000 people saw the play, and it had an impact. The church stopped preaching about the evil of children, and the parents in Kinshasa began to understand the issue.

That’s how the government starting to target me in 2015. I was kidnapped, put in a detention cell for seven days, tortured, and almost killed.

Could you talk about your imprisonment and how you escaped?

That place was in the darkness, no food, no water. Every night they had to bring more people in, so every morning, they had to take out people and kill them. They didn’t call you by your name; just came in and took someone. On the seventh day, they grabbed me and pulled me out. The executioner shot three other people. When it was my turn, he said, “I cannot kill you,” because he recognized me from my play. He said, “I cannot kill you because I know you.” So, my play saved my life.

How and why did you translate that experience into the play Requiem for an Electric Chair?

I began writing about what had happened: how I felt, the feeling of someone before execution, the last two seconds before they die. I felt that. I can talk about it. Requiem for an Electric Chair is the story of my journey in that little cell where I was sequestered for seven days.

I want to relate my story and the story of people who still live in those kind of places in Congo and all around the world, and here in the United States, too, and for people who are ignoring that those kind of places exist.

Why did you decide to represent the other prisoners in the play as human-sized mannequins?

On the first day, I was standing and walking. On the second day, I was just sitting. The third day, sitting but more weakly. The fourth, fifth, until I was lying down. I decided to represent the other people who were with me by mannequins in the different positions I took in that place.

How did audiences receive the play?

Requiem premiered at the 2019 Festival. It sold out two times. It’s going to be in Kennedy Center in November and then in Portland, Maine. Some audiences had compassion for what they saw and heard, some were interested to know more about my journey, and others wanted to know more about the Congo. The reception was very good—but my voice is more important than the play.

Why do you feel it's important for artists to connect with their communities?

I see artists with studios in New Haven who do not go outside. If you go to their studios in two years, you're going to see the same work because they are not connected to the outside; they are still inside the bubble. That’s why it’s important to go outside; by going outside, we bring new perspectives inside, and our work grows.

What are some of the things you've done in the New Haven community?

I developed one program called Human in Plural, Plural in Human. I drew bodies and people wrote on the drawing how different parts of their body help them to exist. It's interesting that on the drawing, nobody could see the size of their bodies, skin colors, origins, languages, religions—but you could see how similar we are.

What's next for you?

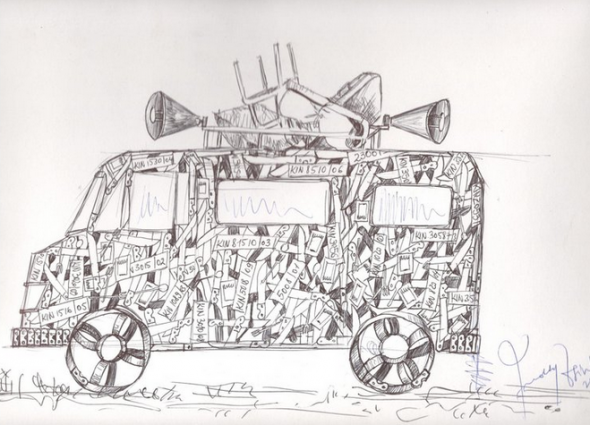

My next project is Surface III. I’ve been working on Surface--with Surface I and II--since 2011. What I want to do here in happening inside of a bus; we will decorate a bus with objects of violence, like machine guns, knives, machetes. Inside will be an empty space where we will have a discussion. People will have a real conversation about who they are, where they are from, what they think about their communities.

How do you want people to respond to you and your work?

The more they have compassion for me, the more they are going to hold me back. The more they move forward with me, the more we’re going to move in parallel. So the audience is even more important than my work; it's not just how they react to it, but how they find their part in my work that is important.

The last line of my play is: I don't need compassion; what I want is for people to look in the spaces like the cell I was held in, in this country and across the world. And I'm asking people if they are ready to do that. Because me, I'm ready.